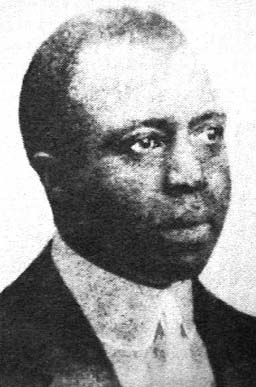

Scott Joplin

Born: November 24, 1868,

probably near Marshall, Texas

Died: April 1, 1917,

New York, New York

|

|

Scott Joplin

Born: November 24, 1868, probably near Marshall, Texas

Died: April 1, 1917, New York, New York |

|

Joplin’s biggest success, by far, was his still famous "Maple Leaf Rag." In the days before radio and records, music popularity was judged by sheet music sales. The "Maple Leaf Rag" sold over one million copies during Joplin’s life and continues to be one of the most popular works for piano in our time. Besides rags, Joplin also wrote waltzes and marches for the piano. These were also popular styles in his day. The Piano Music of Scott Joplin When Joplin started writing his piano rags, the "rag" was a style of popular music known for it’s ragged rhythms and catchy melodies. The standard rag of his day had three parts and an unsophisticated harmonic structure. Most ragtime pianists played by ear and were entirely self-taught. As a youth Scott Joplin took lessons from a German musician who taught him how to read and write music and introduced him to classical piano works from Europe. Joplin’s goal with his rags and other works for piano was to write works for the piano that were on the level of the European classics. Thus he wrote four part rags with sophisticated harmonies, key changes, and rhythmic structures more complex than those of the standard rags of his day. Joplin said that he was strongly influenced by the piano music of Chopin.Joplin always published a note at the top of his rags to remind the pianist not to play them too fast. Apparently it was common for musicians of his day, as it is today, to play rags really fast in order to wow an audience. Joplin probably had two gripes with this practice. First, piano rags were used for dancing in his time and would become undancable if played too fast. Second, playing them too fast would obscure some of their melodic and rhythmic subtleties. Scott Joplin’s Operas Some music reference books incorrectly state that Scott Joplin only wrote one opera, Treemonisha. In fact, he wrote two operas. He wrote the first one, A Guest of Honor, in 1903 and performed it in a tour of Nebraska, Iowa, Illinois, Kansas, and Missouri with "Scott Joplin’s Rag-Time Opera Company." The tour ended quite suddenly and tragically when the troupe’s entire proceeds were stolen in Springfield, Illinois. Unfortunately, the score to A Guest of Honor has long been lost, although parts of the opera may have survived as independent works. Joplin never managed to raise enough funds to support a complete performance of Treemonisha, his second opera. The closest he came was with a non-staged performance in Harlem for a few friends and potential backers. The opera tells the story of Treemonisha, a young African-American woman who becomes the leader of her community and uses her education to lead her people from darkness and superstition towards reason, and advocates non-violence. Treemonisha is quite likely based on Joplin’s second wife who had a great impact on his life and music. Very little is known about her, but it appears that she was well read, and a proponent of women’s rights and African-American culture. One can see why Joplin was unable to find any backers in 1911 for such a radical story. T. J. Anderson orchestrated Treemonisha in the 1960’s and Gunther Schuller orchestrated it again in the 1970’s. Joplin won a special Pulitzer Prize in 1976, in part because of this opera and his special contribution to American music. Joplin’s Orchestral Works Besides his two operas, Joplin also apparently wrote a symphony and a piano concerto, probably in 1916, towards the end of his life. Both were misplaced in the 1950’s by careless heirs who didn’t realize the value of the unpublished manuscripts and quite possibly disposed of them as trash. Joplin’s final orchestral score for Treemonisha was also among the manuscripts that disappeared. The version of Treemonisha that we have today is an earlier piano and vocal score that was published with the hope of attracting funding prior to completion of the orchestration. It lacks many improvements Joplin made later. The missing manuscripts have never been found and are probably gone for good. It is quite possible that Joplin never actually attended a grand opera performance. He was apparently introduced to Wagner’s music by a German Choral Symphony director in St. Louis in 1901. When Joplin heard that Wagner wrote both the words and music, and produced his own performances, he decided that he could do that as well. Joplin claimed that the melody for "Alexander’s Ragtime Band," a big hit in 1911 and one of Irving Berlin’s early successes was stolen from Treemonisha. Joplin had shown Berlin the score to Treemonisha when Berlin was working for a major publisher in New York. Berlin filed for his copyright before Joplin could copyright Treemonisha. Joplin claimed that he then had to re-write the stolen melody, one of the main themes of the opera, so as not to infringe on Berlin’s copyright. Berlin denied all accusations. Joplin’s First Biography Some music reference works contain significant errors regarding Joplin’s life and works. Many of these errors can be traced back to Joplin’s first biography, They All Played Ragtime, by Rudi Blesh and Harriet Janis, which was published in 1950. This book rode in on the waves of the first ragtime revival (1940’s). It was an enthusiastic and respectful account, largely based on interviews with surviving ragtimers and their relatives – such as Joplin’s students, friends and family. Later research (1970’s-1990’s), however, uncovered numerous factual errors. Some of this was due to the faulty memories of the various old-timers who had been interviewed, and some of the errors were due to the biographers not digging deep enough. Many important sources of information on Joplin’s life, such as newspaper articles, were not even checked. This biography did wonders for Joplin’s musical reputation at the time, but unfortunately it was extremely influential and became the definitive "source" for information on Joplin and ragtime. Many of the factual errors from this book have been perpetuated by being passed from book to book and thus continue to appear in reference works. A common error from this biography is the statement that Joplin was married twice. In fact, it appears that he married three times. His second wife died shortly after their marriage. She is very significant to the Joplin story, however, because the main character in Treemonisha was probably based on her. Webmaster of The Unconservatory

|